A proper blogger would have already written up an entire post and made it live the moment the lunar eclipse of January 20/21 2019 was over. The only problem with that is that if you don’t take the time to analyze your data, you could miss something amazing. I would have suffered that fate had I not waited. Without further ado, let’s get into it

The moon was scheduled to pass into the shadow of the earth starting around 10:30 EST. The interesting bit is that during totality of a lunar eclipse, the moon is technically, 100%, full. Meaning that if draw a line from the sun to the earth to the moon, it would be straight. Ironic that it’s also blocked by earth, eh? This particular eclipse was nice because of the timing. It was due to be full and reach totality at roughly midnight, local time. Also, it was a “supermoon” meaning it was at/near perigee in its orbit around the earth. Lastly, it was a “Wolf Moon”, so named for the time of year in which it occurs. I guess? Yep, it was a Super Blood Wolf Moon. How could one not want to step outside to see that unfold?

I gathered my gear, a humble Panasonic FZ70 (superzoom) and a sturdy tripod. Armed with that and my years of photographing the moon, I figured I’d shoot in the very clunky manual mode. Automatic mode gets spazzy when it comes to focus and exposure of partially lit moons. I began shooting at first contact and would continue to shoot every few minutes until totality. I won’t go into the details of every single photo. I’ll get to it and post the progression.

Why am I posting that image so soon? There’s far more to this than just some neat images of the moon being in shadow. You see, while I had been shooting stills for most of the night, something compelled me to shoot a few minutes of video during totality. It was about 8 minutes of total video footage. I thought nothing of it and that it held almost no value. I almost deleted it but got sidetracked. Later the next day I learned of something extraordinary; an impact event during totality. WHAT?

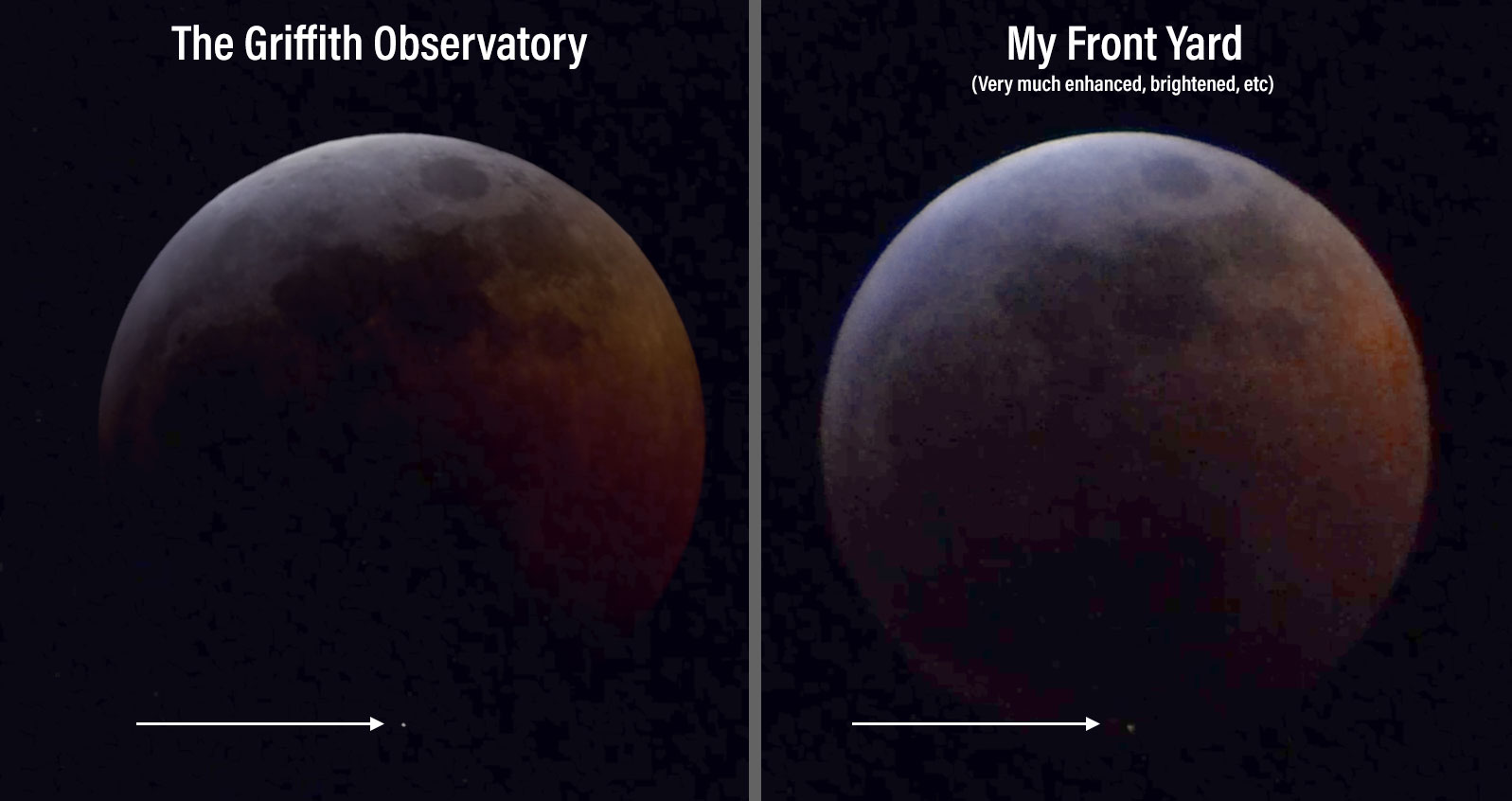

I was at work when I read this and didn’t have access to my video footage. After a few agonizing hours, I finally got to my computer and pulled up the footage. It wasn’t anything spectacular by any means but maybe it was there. Maybe. I had to take it into Premiere to go frame by frame. Yep, 8*60*30 frames. 14,000+ frames. It all looked the same. This was going to suck. The first pass yielded nothing. Time to adjust my levels and make everything brighter. It had to be there as the lighting was identical to the Griffith Observatory image. About 1/3 of the footage is me knocking the camera around so that footage was out. The initial footage also had the lower part of the moon partially obscured. It was cold and hard to keep it centered! Anyway, I figured the best part of the footage was going to be the last 2 minutes or so. There I was, advanced the footage frame by frame, sometimes skipping a few because, yeah, it wasn’t exciting at all.

Sadly, there was nothing in my footage, after all.

I’m totally joking. I wouldn’t write all that up there if I hadn’t found anything. Nope, I managed to scrub past an area that caught my eye. I scrubbed back and forth and there it was. It was one single frame of a tiny distinct ‘pop’ of light. I was elated but I had to make sure it wasn’t just an artifact or sensor noise. I gathered the image from Griffith and overlayed it. It was a bang on match. How amazing is that? Out of sheer luck on top of more luck, I caught that impact event. It was all the buzz as several others had caught it too. My meager 1080p, grainy footage wasn’t anything spectacular, visually, However, the impact was there and I was, well, over the moon.

I was grinning ear to ear after finding that. All that cold? Worth it.

As one last hurrah to the event, I took a few images and spliced them together to simulate a time lapse. Seriously, it’s only 9 images. It does give a sense of how it unfolded over a couple of hours though.

Lunar eclipses aren’t as dramatic as their solar counterparts. That said, they’re unique and special in their own way. They also let you see things you might not otherwise have seen such as stars and, in particular, that impact. A full moon would have been far too bright to easily detect that.

Keep looking up.